Fritz Haber’s life is a compelling narrative of brilliance intertwined with horror. His scientific achievements were monumental, laying the groundwork for modern agriculture and impacting billions of lives. However, his legacy is marred by his role in chemical warfare during World War I, which transformed the nature of conflict and led to immense suffering. This duality in Haber’s life reflects a broader theme in the history of science: the potential for human innovation to serve both noble and nefarious purposes.

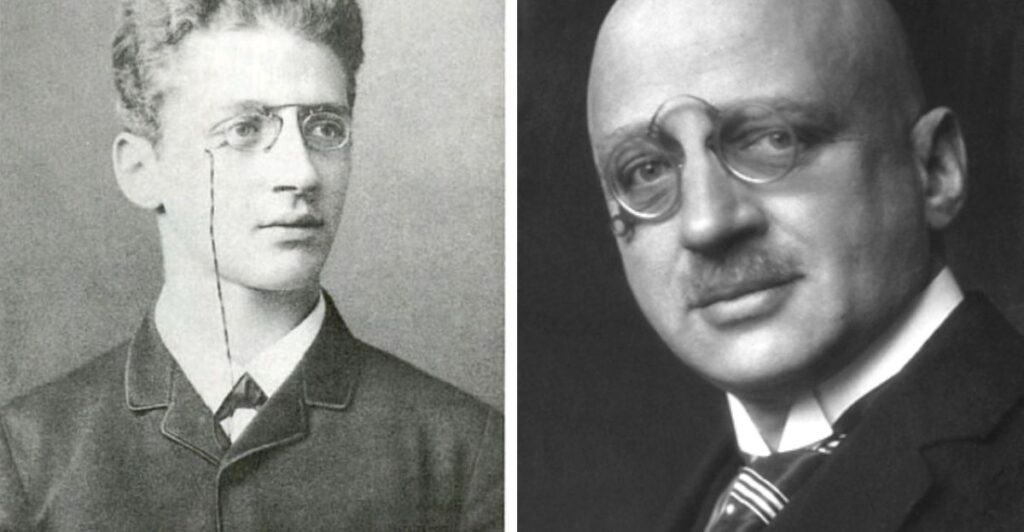

Early Life and Education

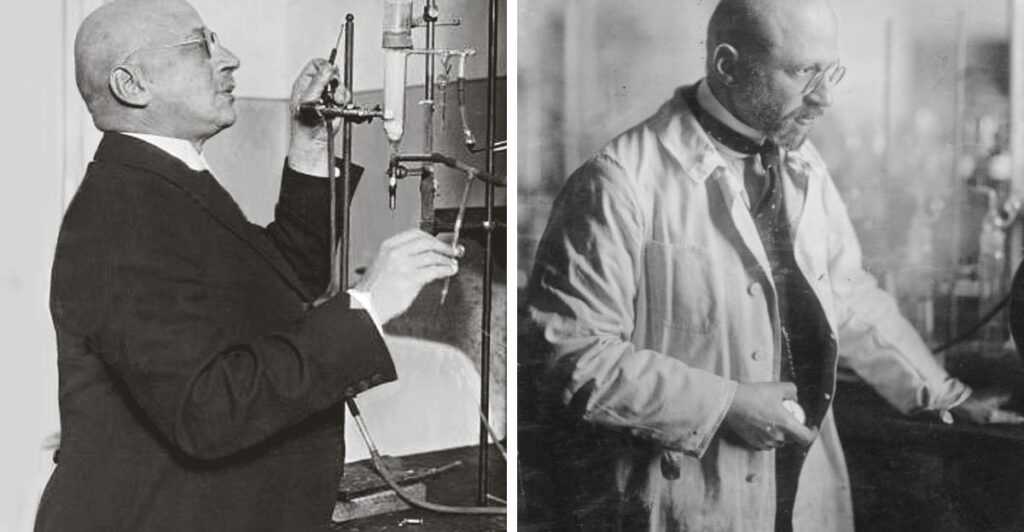

Fritz Haber was born in 1868 in Prussia to a prosperous Jewish family. Growing up in a liberalizing Germany, he was among the first generation of Jews to experience life without the legal discrimination that had historically plagued his ancestors. Embracing this newfound inclusiveness, Haber took great pride in his German identity, famously stating, “[Jews] want only one limit, the limit of our own ability.” His exceptional abilities soon became evident as he pursued higher education in chemistry.

The Nitrogen Crisis

In the 19th century, the demand for nitrogen-based fertilizers surged due to advancements in agricultural science, particularly from chemist Justus von Liebig. Nitrogen was recognized as a crucial nutrient for plant growth, leading to an increased reliance on natural sources like guano and potassium nitrate. However, by the early 20th century, experts predicted that these sources would soon be depleted, potentially leading to catastrophic food shortages as the global population continued to rise.

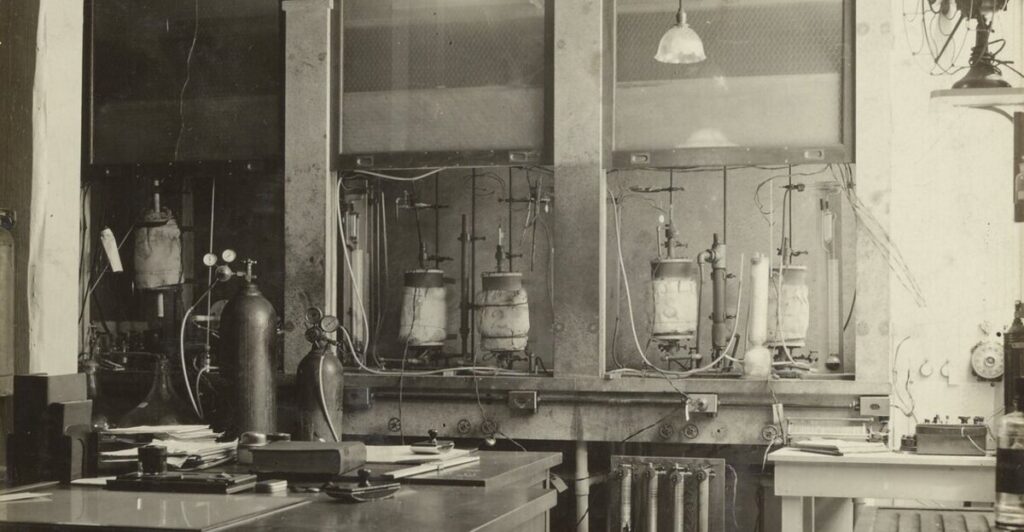

The Haber Process

Amidst this looming crisis, Fritz Haber developed a groundbreaking method for synthesizing ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen through what is now known as the Haber process. By subjecting air to high temperatures and pressures in the presence of hydrogen, Haber was able to produce ammonia on an industrial scale. This innovation revolutionized agriculture and allowed for the production of synthetic fertilizers, fundamentally changing food production worldwide. Today, it is estimated that half of the nitrogen in human bodies can be traced back to Haber’s work.

Personal Life and Ambition

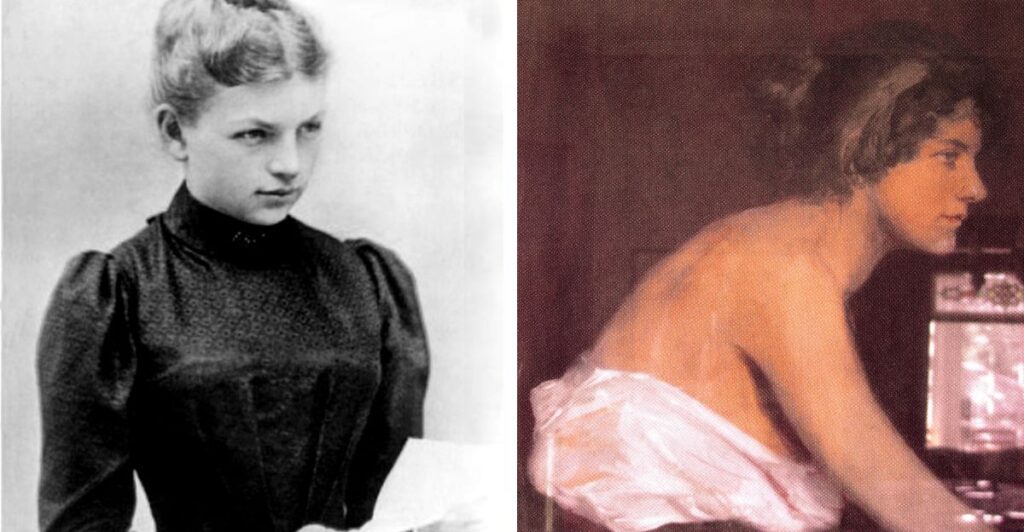

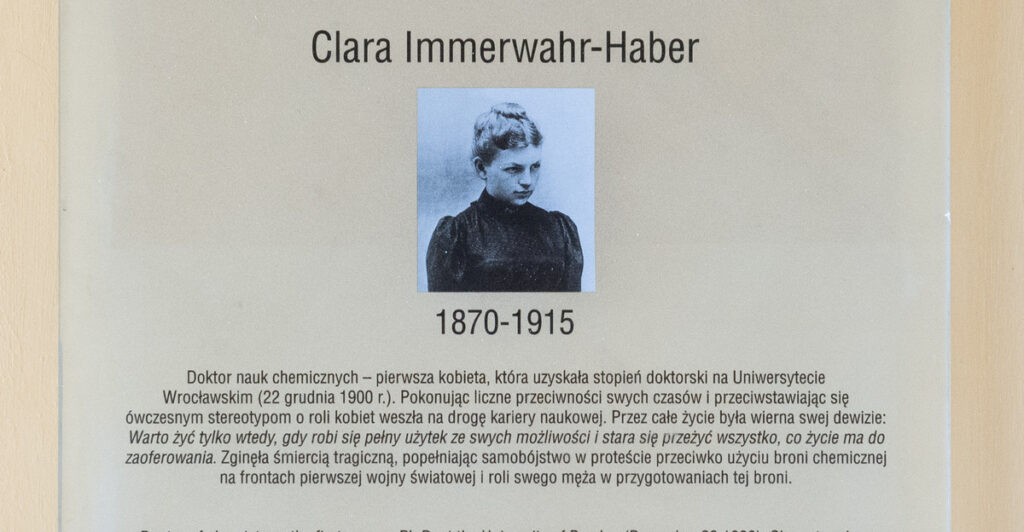

As Haber’s fame grew following his scientific breakthroughs, so did his ambition. In 1890, he began teaching chemistry at a university and met Clara Immerwahr, a fellow chemist who valued her independence. Their marriage faced challenges as Haber’s ego expanded along with his career; he often neglected his family for professional pursuits. Despite their differences, Clara supported Fritz’s research while establishing her own identity in the scientific community.

The War Effort

With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Haber felt compelled to contribute to Germany’s war efforts. He believed that his scientific expertise could help break the stalemate on the Western Front. Promoted to army captain, he led initiatives to develop chemical weapons, ultimately earning him the title “Father of Chemical Warfare.” His fervent nationalism overshadowed any ethical concerns regarding the use of such weapons.

The First Gas Attack

In 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, Haber orchestrated one of history’s first large-scale poison gas attacks using chlorine gas. On April 22nd, he personally signaled the release of approximately 170 tons of chlorine gas against French troops. The attack caused widespread panic and suffering among soldiers who were unprepared for such a horrific weapon. Thousands succumbed to its effects as they experienced agonizing deaths from suffocation and lung damage.

Personal Tragedy

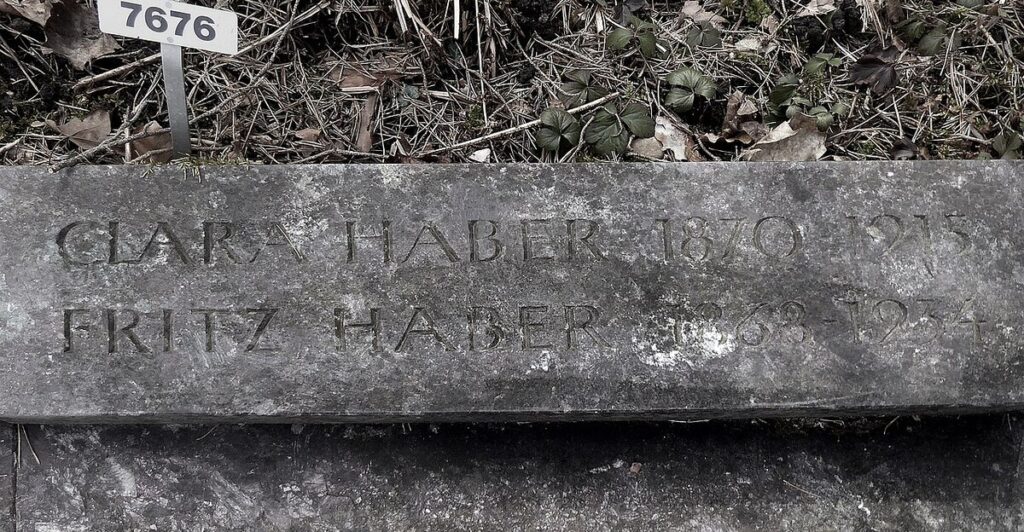

Clara Immerwahr’s opposition to her husband’s wartime endeavors grew increasingly intense; she viewed his work as a betrayal of scientific ethics. Following Haber’s celebration of his successful gas attack, Clara took her own life with his revolver. This tragic event marked a turning point for Haber, who returned to chemical warfare despite personal grief. The war ended with over 100,000 deaths attributed to chemical weapons—a grim testament to Haber’s legacy.

Decline and Exile

After World War I, Fritz Haber’s reputation suffered severely as public awareness grew regarding his role in chemical warfare. When the Nazis rose to power in 1933, he faced persecution due to his Jewish heritage. Despite having been celebrated as a national hero, he became a pariah in Germany and fled to England for refuge but was met with scorn there as well. His health deteriorated during this tumultuous period until he died alone in Switzerland in 1934.

A Legacy Marred by Irony

Even after his death, Fritz Haber’s legacy continued to be tainted by irony. The Nazis seized his research materials and inventions for their own ends; notably, they adapted one of his compounds—hydrogen cyanide—into Zyklon B for use in gas chambers during the Holocaust. This transformation from agricultural innovation to an instrument of mass murder underscores a profound moral complexity surrounding Haber’s contributions.

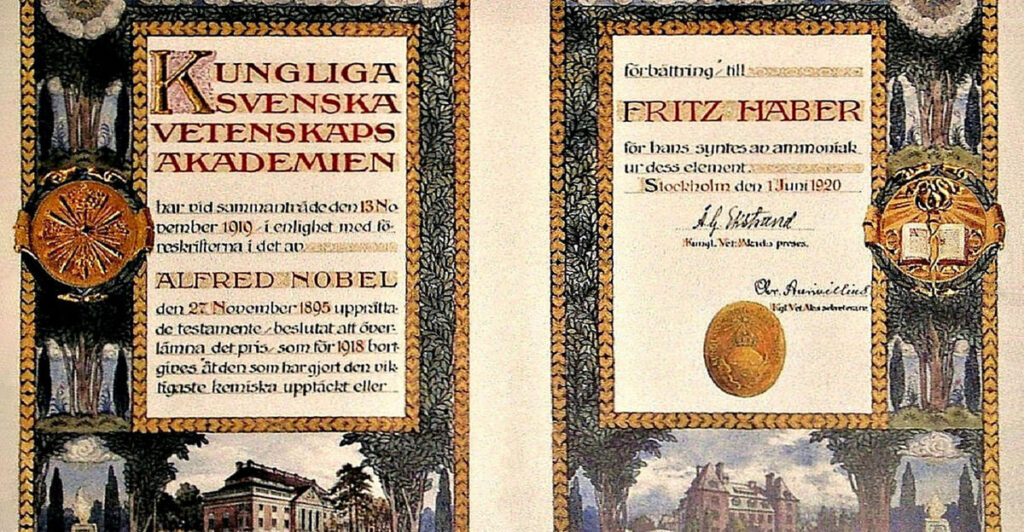

A Complex Figure

Although Fritz Haber won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1918, he remains a deeply controversial figure whose life encapsulates both remarkable scientific achievement and profound moral failure. His innovations have undeniably shaped modern agriculture and contributed significantly to global food security; however, they also facilitated unprecedented horrors during wartime. As we reflect on Haber’s legacy today, it serves as a cautionary tale about the dual-edged nature of scientific progress and humanity’s capacity for both creation and destruction.

References:

Fritz Haber

The Tragedy of Fritz Haber: The Monster Who Fed The World